Why did the CDFCP form?

The CDFCP arose from the recognition of a need for a more strategic and collaborative approach among those involved and interested in conservation efforts in Coastal Douglas-fir ecosystems, and was developed through a series of discussions and workshops including different levels of governments, non-government conservation organizations, and community residents who believe that by working together, we can more effectively achieve our shared conservation goals.

The CDFCP promotes shared stewardship and will identify conservation priorities, reduce duplication of effort, share resources and information, and provide support to its participants.

The CDFCP is led by a Steering Committee and supported by Working Groups focused on different aspects of the CDFCP goals e.g. Securement.

Photo by The Nature Trust of BC

Photo by Lynn Campbell

What is the Coastal Douglas-fir Biogeoclimatic subzone?

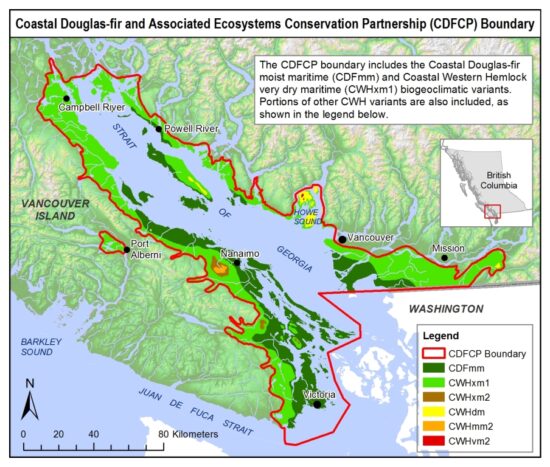

The Coastal Douglas-fir Moist Maritime Biogeoclimatic subzone (CDFmm) is a unique set of associated ecosystems that occurs on a narrow strip of south-east Vancouver Island, portions of the Gulf Islands, and pockets along the south coast and mainland of British Columbia. In this region, in the rain shadow of Vancouver Island and the Olympic Mountains, a Mediterranean-like climate exists, which allows for a rich flora and fauna to thrive. It is important to understand that the Coastal Douglas-fir includes far more than just Douglas-fir forests. In addition to those forests, the zone includes a wide variety of ecosystems, including Garry Oak ecosystems, wetlands, and shorelines.

A more detailed description of the CDFmm can be found in the Ecosystems of British Columbia: Chapter 5 Coastal Douglas-fir Zone.

In 2021, the BC Ministry of Forests also released a series of maps, illustrating the range of the CDFmm in Canada.

What ecosystems are in the CDFCP boundary?

In addition to the Coastal Douglas-fir Moist Maritime Biogeoclimatic subzone, the CDFCP has chosen to include the Coastal Western Hemlock Biogeoclimatic zone, a very dry maritime variant (CWHxm) in its working boundary. The CWHxm has many rare ecosystem types, like the CDFmm. Additionally, some areas outside of the CDFmm and CWHxm have been included because of their integral position within the CDFCP planning area. These areas include components of watersheds and islands that are related to CDFmm and CWHxm ecosystems. The First Peoples Map of BC enables the viewer to access information on all the First Nations languages and communities in BC, including the 63 First Nations with territory in the CDFmm and CWHxm1.

Map of the CDFCP’s working area.

Please note, this map takes time to load. Map representing the 63 First Nations represented in the CDFCP working area. Source: First People’s Map of BC.

Why is the CDFCP Region at Risk?

The CDFCP Region is at risk of losing many of the species, relationships, and healthy ecosystems that define it. Located on southeastern Vancouver Island, small areas of the Lower Mainland and islands in the Salish Sea, the natural ecosystems are competing with human pressures, including development, industrial landscape use, increasing numbers and frequency of invasive species, and increased recreational use. Some of the ecosystems associated with the CDFCP Region, such as Coastal Bluffs, Garry Oak ecosystems, and wetland ecosystems, have lost well over 75% of their former area.

- The Coastal Douglas-fir moist maritime biogeoclimatic subzone (CDFmm) is the smallest and most at-risk zone in BC and is of conservation concern (Biodiversity BC, 2008).

- The CDFmm is home to the highest number of species and ecosystems at risk in BC, many of which are ranked globally as imperilled or critically imperilled (BC CDC, 2012).

- Of all the zones in BC, the CDFmm has been most altered by human activities. Less than 1% of the CDFmm remains in old-growth forests (Madrone, 2008) and 49% of the land base has been permanently converted by human activities (Hectares BC, 2010).

- The trend of deforestation and urbanization continues and has resulted in a natural area that is now highly fragmented with continuing threats to remaining natural systems.

- Approximately 11% of the CDFmm is protected in conservation areas6.

- The extent of disturbance combined with the low level of protection places the ecological integrity of the CDFmm at high risk (Holt, 2007).

Why Conserve the CDF?

The Case for Conserving the Coastal Douglas-fir Moist Maritime Biogeoclimatic Subzone (CDFmm) and the Coastal Western Hemlock, Eastern Very Dry Maritime (CWHxm1) subzones:

- The CDFmm makes up about 0.3% of BC’s total area1

- The CDFmm is by far the smallest and rarest of the 16 ecological zones in BC2

- The CDFmm extends south into the USA but the vast majority of its global range is in BC2

- The CDFmm contains the highest diversity of plant species in BC3

- The CDFmm contains the highest diversity of over-wintering bird species in Canada 4

- Although 94% of BC is public land, 80% of land in the CDFmm is privately owned4

- Approximately 75% of the human population of BC lives in the CDFmm including in major centers such as Vancouver, Victoria, and Nanaimo4

- 48% of the CDFmm and 32% of the CWHxm1 is occupied by human-dominated (urban, agriculture, mining, etc..) land cover1

- Approximately 40% of the CDFmm occurs in forests of various ages which historically have been used for forestry. Less than 1% of old-growth (>250 yrs) CDFmm forests remain5

- Approximately 11% of the CDFmm is protected in a variety of private and government conservation lands6 making it the least-protected ecological zone in BC

- The CDFmm includes Garry oak ecosystems, of which less than 5% remains in a near-natural condition3

- The CDFmm contains more species at risk than any other ecological zone in BC2 (25 globally imperilled species and >225 species that are provincially imperilled or threatened)7

- 98% (42 of 43) of the ecological communities in the CDFmm are considered “at risk”7

- More than 151 introduced invasive species exist in the CDFmm8

- The CDFmm has the highest road density of any ecological zone in BC1

1 Hectares BC query (http://www.hectaresbc.org/app/habc/HaBC.html ). Accessed May 2013

2 Austin, M. A. et al. 2008. Taking Natures Pulse: The Status of Biodiversity in BC – Biodiversity BC

3 Ward, P., G. Radcliffe, J. Kirkby, J. Illingworth, and C. Cadrin. 1998. Sensitive Ecosystems Inventory: East Vancouver Island and Gulf Islands 1993-1997. Volume 1: Methodology, Ecological Descriptions and Results. Technical Report Series No. 320. Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region, BC

4 Floberg, J., M. Goering, G. Wilhere, C. MacDonald, C. Chappell, C. Rumsey, Z. Ferdana, A. Holt, P. Skidmore, T. Horsman, E. Alverson, C. Tanner, M. Bryer, P. Iachetti, A. Harcombe, B. McDonald, T. Cook, M. Summers, D. Rolph. 2004. Willamette Valley-Puget Trough-Georgia Basin Ecoregional Assessment, Volume One: Report. Prepared by The Nature Conservancy with support from the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Washington Department of Natural Resources (Natural Heritage and Nearshore Habitat programs), Oregon State Natural Heritage Information Center and the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre

5 Madrone Environmental Services. 2008. Terrestrial ecosystem mapping of the Coastal Douglas-fir Biogeoclimatic zone – Madrone Environmental Services

6 NTBC’s Relative Ecological Assessment Tool (2022).

7 BC CDC Species and Ecosystem Explorer (accessed April 2013)

8 MacDougall, A.S., B.R. Beckwith, and C.Y. Maslovat. 2004. Defining conservation strategies with historical perspectives: a case study from a degraded oak grassland ecosystem. Conservation Biology. 18: 455-465